On Sunday, 14 September we had arrived in Dijon, the capital of the Burgundy. We had entered the region in July as we ascended the Saône and we had explored along the Seille, crossed the Canal du Centre, ascended the Loire to its end of navigation, then descend it to the Canal du Nivernais, which we followed to the Canal du Bourgogne and then along it. We had done a clockwise circuit near the boundaries of the Burgundy. The boundaries of present-day Burgundy, one of the twenty-two Regions of Metropolitan France, have changed dramatically over the years.

Human settlement in the area is traced to Lower Paleolithic times and one of the final phases of the Upper Paleolithic is named Solutrean for evidence of the 20,000-year occupation of the site at Roche de Solutré near Macon. The Burgundy region was later an important crossroads during the Bronze Age and waves of migration from Central Europe swelled the population. Predominantly Celtic in origin, these people were called Gauls by the Romans. The Gauls of the area around present-day Burgundy were the last hold-out against the Roman conquest. With the surrender of Vercingetorix to Julius Caesar in 52 BC, the area finally fell to the Romans after 150 years.

In the fifth century, as the Roman Empire was collapsing, the Burgundians moved in from the northeast. Thought to be originally Scandinavian, these peoples had long before settled along the Baltic coast of what is now Germany before migrating and occupying the area that is now eastern France and western Switzerland.

In the sixth century another Germanic tribe, the Francs conquered the Kingdom of Burgundy, but finding the Burgundians strong, they allowed them to continue to occupy and govern the area. The Frankish territory continued to expand for another three centuries, reaching its greatest extent in 814 as the Carolingian Empire under Charlemagne.

After inheritance disputes among Emperor Charlemagne’s three sons following his death, the Treaty of Verdun in 843 divided the empire into three portions: East Francia, Middle Francia and West Francia.

West Francia was a major portion of what would become the present-day France. The dividing line between West and Middle Francia ran through the Burgundy, dividing it into two unequal pieces, the smaller being the Duchy of Burgundy, which is closely equivalent to today’s Burgundy Region.

Starting from this small base, successive Dukes of Burgundy expanded their holdings through battle, negotiation, marriage and inheritance. By 1477 their possessions included much of modern-day Netherlands, all of Belgium and Luxembourg and portions of Germany and Switzerland. This was nearly the size of the lands of the Kingdom of France, but it contained the biggest cities and the richest territories of the region. The court in Dijon outshone the French court both economically and culturally. In Belgium and in the south of the Netherlands, a 'Burgundian lifestyle' still means 'enjoyment of life, good food, and extravagant spectacle’. During the Hundred Years War and the years following it, the Dukes of Burgundy tried on many occasions and through various means to take the crown of France. Duke Charles the Bold was killed in battle in January 1477 in one such attempt.

Louis XI of France quickly moved to seize Burgundy by presenting himself as the protector of Charles’ daughter and heir, Mary. By the beginning of February, the royal army had entered Dijon and occupied the Burgundy. Duchess Mary refused the King’s offer of marriage to his son and heir, the Dauphin Charles.

She retreated north to the Low Countries, and then a few months later she married Maximilian of Austria, the future Hapsburg Emperor, Maximilian I. By 1520 their grandson, Charles V wore many crowns, among them as the King of Spain and the Archduke of Austria and he had been elected Holy Roman Emperor. He was the most powerful monarch of the time, but he focused his efforts on the recovery of the duchy of Burgundy that had been seized from his grandmother. He was successful in regaining only the Charolais, the southwest portion. By this time, many of the loyal Burgundians had moved north to the Burgundian Netherlands and Flanders, taking with them their arts, talents, skills and wealth. During the following century, the Netherlands dramatically increased its standing as the most prosperous region in Europe.

With this background in mind, on Monday we headed into the medieval heart of Dijon. There were dramatic changes since my last visit in 2006. A new light rail transit system opened in 2012 and much of the downtown core had been converted to pedestrian-only streets. What was once a noisy and exhaust fuming traffic gridlock is now peaceful and inviting. There are many medieval buildings and classic Burgundian glazed tile roofs throughout the city centre.

We continued through very pleasant streets to place de la Libération and past l’Hôtel de Ville, the City Hall, which is housed in the former royal and ducal palace buildings.

Through a side entrance toward the rear of a building, we entered the transept of the former église Saint-Étienne. The church was confiscated after the Revolution and became the wheat market, later the stock exchange. During renovations in the choir, remains of the Roman castrum was found beneath the floors.

This city wall was built between 270 and 275 by Roman Emperor Aurelian. It was ten metres high, four-and-a-half metres thick and with its thirty-three towers and four gates, it circled twelve hundred metres around the city. Very few traces of it remain.

We walked back to place de la Libération and its imposing buildings. The palace of the Dukes of Burgundy and later the Kingdom of France is comprised of several interconnecting parts. Among the oldest parts are the Gothic style ducal palace from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, most prominent being la Tour Philippe le Bon. The remainder of the buildings date from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and are in the Classic style.

Inside the courtyard we approached la Tour de Bar, which had been built by Philip the Bold in 1365. Beside it is the entrance to le musée des beaux-arts de Dijon, which was established here in 1787. It is one of the finest, most important and oldest museums in France. We were delighted to find that admission is free.

Among the more important pieces in the museum are the tombs of the Dukes of Burgundy. Philip the Bold built a Carthusian monastery at Champmol, just outside Dijon to house the tombs of his dynasty. He gathered many artists to decorate and embellish its interior and to work on his tomb featuring his recumbent effigy. Work on it began in 1381.

Three successive sculptors, Jean de Marville, Claus Sluter and Claus de Werve worked on it for thirty years, completing the project in 1410, six years after Philip’s death. The polychrome and gilt decoration was done by Jean Malouel, official painter to the Duke. The tomb is considered to be one of the finest works of Burgundian sculpture.

Philip’s heir, John the Fearless expressed a wish for his own tomb to resemble that of his father, but as a double one with his Duchess Margaret of Bavaria by his side. Work had not been commenced when he died in 1419. Finally in 1443 a Spaniard, Jean de La Huerta, was contracted and was sent drawings for the effigies. He completed most elements, but not the effigies, before leaving Dijon in 1456. Another master was brought in, and in 1470 the monument was finally installed.

Remarkable about the two tombs are the mourners standing in alcoves surrounding the bases of the biers. There were originally eighty-two of these free-standing alabaster sculptures, each about forty centimetres high and each an individual character. Following the Revolution, the tombs were badly damaged by anti-royal vandals and a dozen of the mourners were stolen. Some ended up in Dijon homes, others were marketed to museums and private collectors.

In 1819 the tombs were restored and placed in the Dijon museum. In 1945 an English collector returned a choirboy sculpture to Dijon. Soon after, the Louvre donated its mourner and the Cluny Museum returned two mourners. An American collector had bought four mourners from French collectors and after his death, his estate sold the sculptures to the Cleveland Museum of Art, where they remain today. In 1959 the museum gave replicas of its mourners to the Dijon Museum. Only two of the niches remain empty and it is presumed the missing sculptures had been destroyed during the vandalism of the Revolution.

Among the museum’s vast collection of medieval art are many pieces from the monastery at Champmol, including a splendid folding altar piece. It was carved by Jacques de Baerze and gilded and painted by Melchior Broederlam.

The quality of the 1398 painting on the exterior of the door panels is superb, particularly the scene of the Annunciation.

In addition to the medieval collections, the museum has a large collection of ancient Egyptian, Greek, Etruscan, Gallic, Roman and Byzantine material. We were more interested in Burgundian art, so we skipped through these quickly and on to the galleries of Renaissance and later sculptures and paintings.

Peter Paul Rubens is well represented among the Burgundian Netherlands and Flemish artists, and the pieces in the museum arrived under interesting circumstances. During the conquest of the Austrian Netherlands by the armies of the French Revolution, paintings were seized in 1793 and 1794 from churches in Flanders. Two of these were transferred from the Louvre to the Dijon museum in 1803. These were the side panels from a triptych altar piece commissioned in 1632 by a parishioner to honour her dead father. One was “The Entry of Christ Into Jerusalem”.

The other is “Christ Washing the Feet of the Apostles”. These two side panels were painted on wood and appear to have been rather quickly rendered. At one time thought to have been produced by Rubens’ workshop, experts now believe they came directly from the master’s hand.

The central panel of the triptych is “The Last Supper”, which measures three metres by two-and-a-half, is oil on canvas and is decidedly more meticulously painted. It is now in Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan.

A brochure on Rubens produced by the Dijon museum reads: “One of the greatest masters of Flemish painting, has always been admired in France. The three tables in this room, seized by French troops in 1794, are representative of that interest. They also reflect the final changes in the seventeenth century on the medieval form of hinged altarpieces.”

This altar, composed of a central panel flanked by two movable flaps, was commissioned in 1618 by the tailors' Guild in Lierre, near Antwerp for their chapel. It was seized in 1794 by French troops, and arrived at the Louvre. It was dismembered in 1809 and the central panel was sent to Dijon. The side flaps remained at the Louvre and were claimed in 1815 and had to be returned to Lierre. We wondered why these other stolen Rubens pieces are still displayed in Dijon.

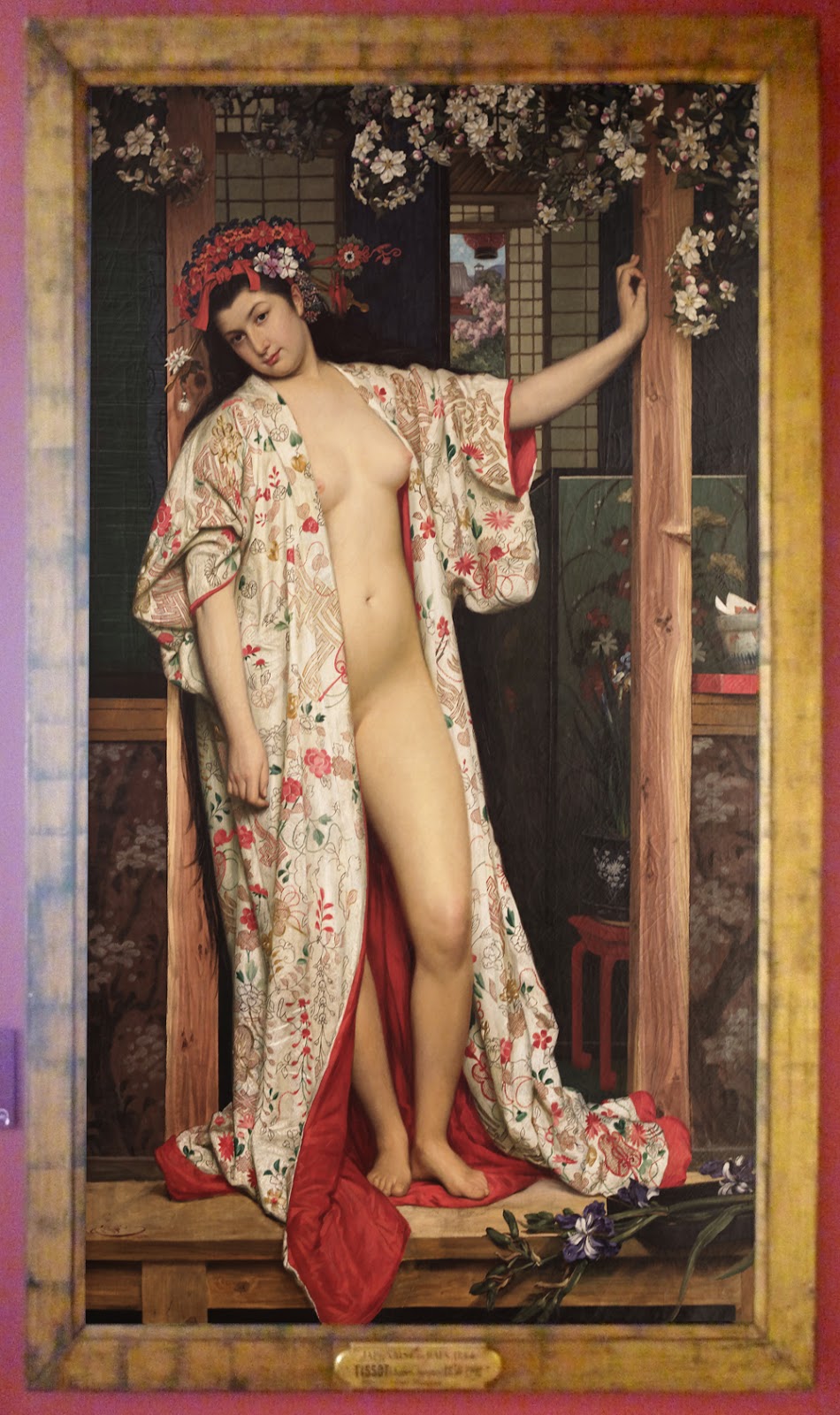

We slowly made our way through the galleries, looking at seventeenth and eighteenth century European works and then we wandered through a grand assortment of paintings by the nineteenth century French painters, including Delacroix, Courbet, Tissot, Monet, Manet, Sisley and Pissarro. We found "la Japonaise au bain" painted in 1864 by James Tissot a refreshing departure from the heavy religious themes we had been viewing.

As we made our way out from the museum and back toward Zonder Zorg, we reflected that this region was once the principal centre of art and culture in Europe. Since the departure of the last of the Dukes of Burgundy, the region has lost this reputation, but through their continuing refinement of viticulture and viniculture, when the word Burgundy is spoken today, most think of great wine. Many of the world’s finest Pinot Noirs and Chardonnays come from here, but that’s another story.

No comments:

Post a Comment